Freedom in freediving

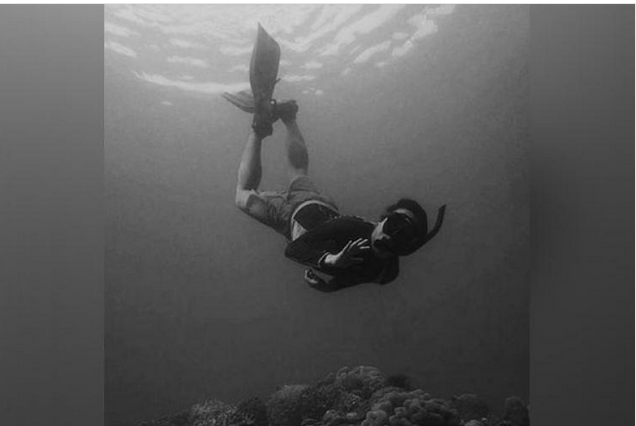

HOW long can you hold your breath? Training in the art (and sport) of freediving, I have learned that the usual urge to breathe comes between one and one 1/2 minutes, and it is a mental challenge to overcome it. There is a certain peace and quiet when you’re underwater down to more than 10 meters (more than 30 feet) – still shallow to many freedivers – and in my first time to descend around this depth and to feel that I no longer crave for air, this peace of mind became a euphoric feeling. It felt like freedom, it’s almost being suspended in flight, and my body has become part of the ocean. Yet my personal record time is just one minute and 30 seconds, and depth of 16 meters. I still have to conquer a lot of physical challenges to go deeper and longer. My limits are negligible to the current freediving world champion Herbert Nitsch who has gone down to 214 meters (700 feet!) or Tom Sietas who held his breath for 22 minutes and 22 seconds. I learned through my instructors that the mental urge to breathe will momentarily disappear since we do not lack oxygen anyway (it’s in our blood!), but the physical need to expel the concentrated carbon dioxide in the body will become stronger through the contractions of the diaphragm. It’s like a series of hiccups that signal a freediver to calmly head back to the surface. Every freedive is an attempt to understand the mammalian dive reflex, similar to what dolphins and whales have, and this is what captivates me about the experience. I have learned to embrace this feeling, surrender to it, sometimes push my limits, but ultimately to listen to my body and naturally come back for air. Once I’m back at the surface with hook breaths to recover, I long to go deeper and longer again the next time.

But why? Where is this motivation coming from? What pushes freediving athletes to conquer depths or breath-holds unimaginable to human nature? What pushes ordinary (mostly non-athletic) people like me to freedive? I was very fortunate that my Aida certification in freediving was part of a scholarship program by Kapit Sisid: Freediving for Marine Conservation. Kapit Sisid envisions Philippine coastal communities to be “aware of the role of their marine resources in their economic development and overall wellbeing. It uses the sport of freediving as a communication tool to achieve this – how can you appreciate something that belongs to you if you have never seen it with your own eyes”? These words are from Tara Abrina, Philippine national record holder in freediving, and a research officer at the University of the Philippines-Marine Science Institute. Tara led Kapit Sisid which started out as a project by Reef Nomads Skin Diving Tours and Manumano Freediving when they did work in Ipil, Zamboanga Sibugay. Her in-depth knowledge on both sides has allowed her to connect freediving schools to coastal communities or NGOs that have been working to protect the ocean and vice versa. This approach is seen in the two projects Kapit Sisid has accomplished so far: the Ipil project and the Freedive Panglao project. While the former focused on a group of reef managers in Ipil and trained them to be internationally-certified freedivers, the latter brought reef managers from all over the country to train and get certified under one school in Panglao, Bohol. Through a selection process, I was able to join the Freedive Panglao project because of my role then as Island Manager for Danjugan Sanctuary. My objective was to be better in skin diving for regular underwater assessments and more importantly, for safer snorkeling sessions with kids (and adults) when we conduct our Marine and Wildlife Camps. I was also eager to pass what I learn to the people I work with, although now I know that locals who have grown up fishing could obviously dive deeper and longer, albeit with differences in methods. Being almost always in the water, being a certified freediver will nurture my sense of responsibility for our conservation and environmental education work. As I was making my way to the training (held at Freedive Panglao, Bohol, from November 29 to December 1, 2016), I caught a cold. The timing couldn’t just be worse. I know congestion will prevent proper equalization and will make it difficult for me to dive deeper. I normally do not use pharmaceuticals to deal with a cold, but for this trip I took everything that could decongest my sinuses fast. Then I met my fellow freediving trainees – all of them deserved the six slots of the sponsored training. They were passionate about conservation and how freediving could support their work. What surprised me is that the training was more like a meditation or yoga retreat. Our instructor Stefan Randig was like a Zen master. When he talked about preparing to freedive, he made sure we understand by heart that relaxation is key. Calming the mind, being “one with the water,” and watching your breath – these were our mantras. I didn’t feel I was training for a sport. But the actual exercises in the pool and open water were very challenging of course – especially with my congestion, it was difficult to equalize, and I think the pressure started a toothache! I wasn’t having problems with the breath hold, maybe because I have a background in meditation – but I had pain piercing through a molar every time I went deeper. Eventually, the depth or the time of my dives did not matter anymore. It is true, what Stefan taught us, that the important thing is we relax and enjoy the dive. This mindset was extremely important to the extreme sport of freediving. And enjoying the dive, as Kapit Sisid advocates for, would also mean caring about the ocean more. Freediving could be a strong expression of our love for the marine world. And finally, “freedom.” Those who have been freediving know this is what we’re all about.

SOURCE: http://www.sunstar.com.ph/bacolod/lifestyle/2017/06/27/freedom-freediving-549721